Craniobot: A computer numerical controlled robot for cranial microsurgeries

“The whole idea is to keep the sharp edge as long as possible,” said Magee. “For example, aluminum is very abrasive and it will wear off an insert corner when the process is run at high RPMs or high surface feeds. But if you can keep the sharp edge, you can continue the cut and keep a good tolerance.

Sue Roberts, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. A metalworking industry veteran, she has contributed to marketing communications efforts and written B2B articles for the metal forming and fabricating, agriculture, food, financial, and regional tourism industries.

“Whether formed from high-speed steel, cobalt, or tungsten carbide, uncoated tools can be used on non-ferrous and ferrous materials,” said Harvey Patterson, product development engineer at Scientific Cutting Tools Inc. “That being said, they typically work better on non-ferrous materials that create less heat and pressure, both of which deteriorate the cutting edge during the cutting process. The cutting edge pressure is dictated by the strength of the material being machined.”

Avery small B2C company - not vat registered Copyright © 2024. All Rights Reserved. Ecommerce Website Design by ShopWired

The aerospace industry, shops producing plastic moulds and dies, and applications that require tight tolerances, like ± 0.0005, and fine surface finishes are preserving the niche for uncoated inserts among their coated counterparts.

“Another reason to use uncoated inserts is to avoid putting too much cutting pressure on thin-walled parts. With thin-walled parts, too much pressure can cause them to cave in or move. In these applications, you want to use an uncoated insert with a real sharp edge.”

“Everyone wants to cut faster and quicker, but I don’t know that it is better when you need perfection. There is still a place in manufacturing for uncoated, highly polished, fully ground inserts.”

Magee said, “Some new coatings can have 26 layers and keep a sharp edge. These are good for production parts that typically won’t be as tight a tolerance as a mould and die. In practical use, manufacturers producing very difficult parts will choose a sharp, uncoated insert because it can hold the size and tolerance that are needed.

JavaScript appears to be disabled in your browser. JavaScript must be enabled in order to utilise the full functionalilty of this website.

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Joe Magee, product manager for gear milling at Vargus USA, said, “Uncoated inserts are good for finishing, projects where you don’t want to put any stress into the part, and avoiding work hardening in the materials. If you cut high-temperature materials too hot or too fast, they will work-harden and cause trouble down the road.

“In a production shop, a coated insert that will last for the predicted wear is needed, but when you are making a one-off part that takes a lot of skill, you need to be able to project what the tool is going to do every time you put it in the machine. No room for error.

Patterson said, “Pressure on the cutting edge combined with heat from friction caused by the material flowing across the surface of the tool can cause built-up edge. This buildup will eventually break off taking part of the tool with it which leads to tool failure.

Some applications or materials, however, or even the desire to increase speed for faster material removal, can generate enough heat that the use of coolants should be considered.

Inserts sans coatings, however, still have their place.An unadorned insert with no coatings that could dull its cutting edge is often the choice when a manufacturer is faced with producing a component that has little to no room for variance from specifications from tough materials like cast iron, high-temperature materials, and heat-resistant superalloys (HRSA).

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of Canadian Fabricating & Welding.

“Uncoated carbide is used a lot in the mouldmaking industry because the moulds are usually one-offs. They are high-value parts, some produced from difficult materials like titanium, and may be worth $20,000 before machining begins. The finished product has to be perfect.”

“A positive rake cuts with less pressure than a neutral or negative rake,” he said. “Think of whittling wood. If the knife blade is at 90 degrees to the wood, it is hard to cut; if the blade is at a slight angle, the cut becomes much easier.”

In addition to their very sharp edges, uncoated inserts contribute to needed perfection by slowing down the production process. A slower surface feed provides more control, and lighter cuts can be taken with the sharp cutting edge.

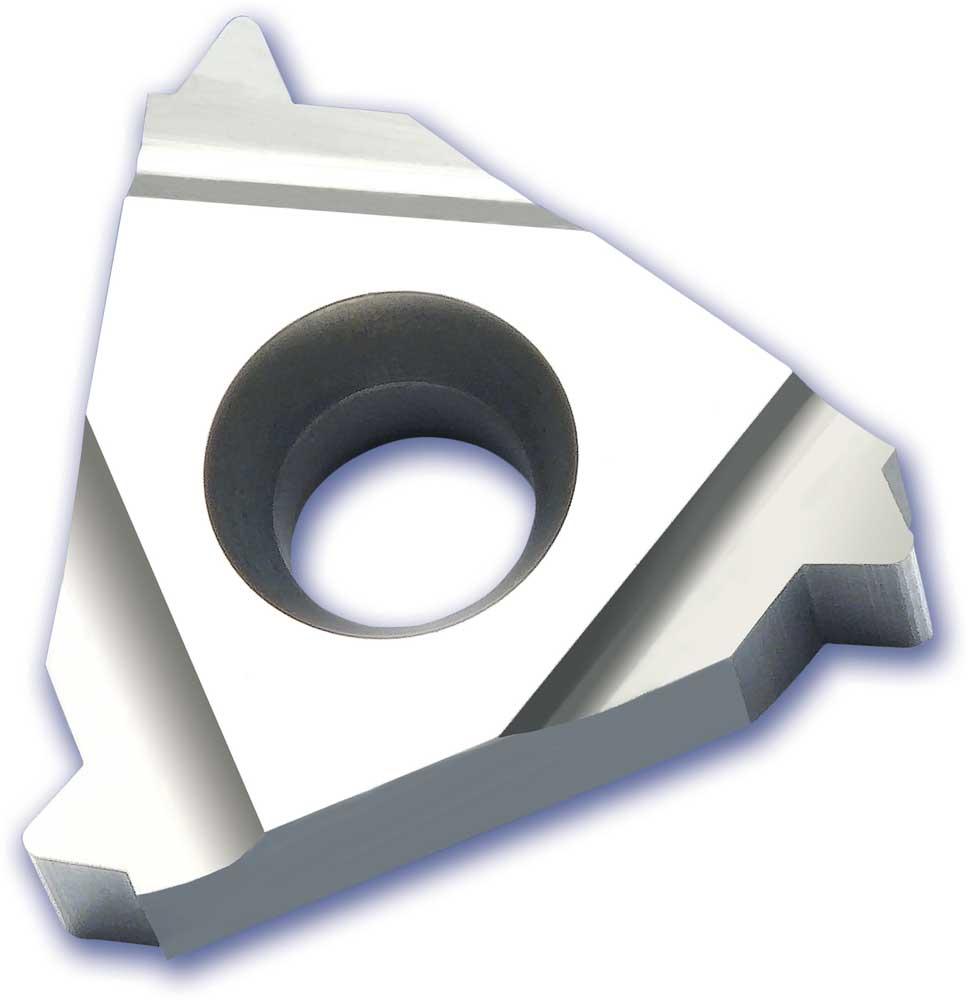

Sharp, uncoated inserts like the VK2 from Vargus are designed for processing non-ferrous material, aluminum, high-temperature materials, and titanium alloys. Photo courtesy of Vargus USA.

“The heat can be reduced by using coolant. Coolant can be easy to apply if machining the outside of a part. When machining an inside, such as when boring or drilling, getting coolant directed to the tool to keep it cool can be more difficult, and coolant-through tools may be needed.”

The MD133 milling cutter offers high process reliability and maximum productivity with an optimal metal removal rate with reduced machining times.

A lower cutting speed that produces less heat helps reduce the risk of built-up edge that eventually breaks off and takes a part of the tool with it. Photo courtesy of Scientific Cutting Tools Inc.

Boring or drilling with uncoated inserts may create enough heat that coolant-through tools should be considered. Photo courtesy of Scientific Cutting Tools Inc.

A constant stream of advanced insert coatings flows from tooling manufacturers to offer increased tool life, better surface finish, characteristics to effectively cut a variety of materials, or custom layers engineered to provide ideal material removal for a very specific material or application.

Reducing that pressure, according to Patterson, is best accomplished by using tools with a positive rake. How positive depends on the material. For example, cutting aluminum will require a very high positive rake; for HRSA or titanium, the rake doesn’t need to be as high as long as the edge remains sharp to avoid placing too much pressure on the part.

A highly polished, uncoated insert like the VK2P from Vargus can produce high-quality surface finishes in aluminum. Photo courtesy of Vargus USA.

Since heat generation is reduced by the lower cutting speed, uncoated inserts can be run dry for most applications, which offers some advantages. “If you are finishing a part with a very tight tolerance, you get a better result cutting it dry. Cutting slow with an uncoated insert gives you controlled insert wear,” said Magee. “With the slow surface feed or speed you really don’t need to use coolant.”

Substrate for uncoated inserts, Magee said, should be ultra-fine or nano-fine with a grain that is less than 1 µ. “Probably, there should be a 3 per cent cobalt binder to keep the very sharp edge. Fewer voids between the grains where the cobalt or another binder can melt keep the edge sharp.

“It’s about cobalt and tungsten carbide and a few other additives—how much a manufacturer puts into what I call pressed dirt. Then it’s about the finish and polish.” Uncoated inserts may lack extra layers of coating, but they are ground to accept a special polish, in some cases to a mirror finish.

18581906093

18581906093