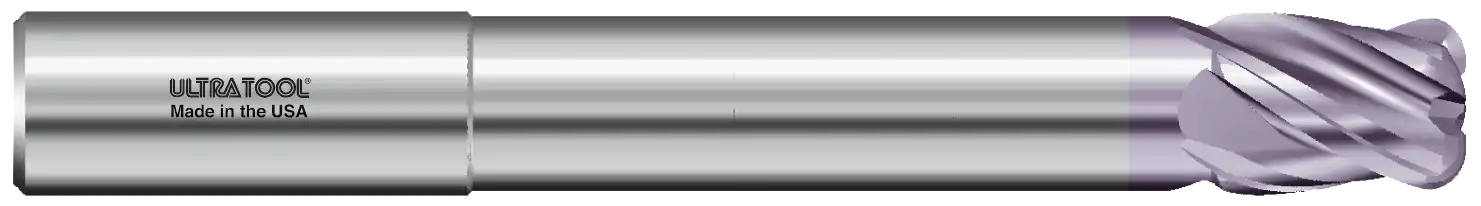

Whether Hogging or Finishing, End Mills Are Up to the Task - carbide end mill

Stainless steels possess high strength, heat resistance, excellent workability and erosion resistance. Four general classes have been developed to cover a range of mechanical and physical properties for particular applications. The four classes are: the austenitic types of the chromium-nickel-manganese 200 series and the chromium-nickel 300 series; the martensitic types of the chromium, hardenable 400 series; the chromium, nonhardenable 400-series ferritic types; and the precipitation-hardening type of chromium-nickel alloys with additional elements that are hardenable by solution treating and aging.

![]()

Secures a cutting tool during a machining operation. Basic types include block, cartridge, chuck, collet, fixed, modular, quick-change and rotating.

WS40PM’s cobalt-rich substrate provides robust fatigue resistance and edge integrity, while the multiphase AlTiN-TiN PVD coating reduces tool wear, making it suitable for a range of high-temp steel alloys, austenitic and PH stainless steels, nickel-based superalloys such as Hastelloy and Nitronic, and titanium.

Depressions formed on the face of a cutting tool caused by heat, pressure and the motion of chips moving across the tool’s surface.

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.

“WS40PM’s advanced cobalt-rich substrate provides robust fatigue resistance and edge integrity, while the multiphase AlTiN-TiN PVD coating reduces wear,” says Mike Sperhake, EMEA-region product specialist for WIDIA. “Using an initial cutting speed of 175 ft/min (53 m/min) we’re seeing 25-35 percent productivity gains and consistent improvement in tool life, even when milling very tough materials like Ti-5553 and Super Duplex steels.”

1. Permanently damaging a metal by heating to cause either incipient melting or intergranular oxidation. 2. In grinding, getting the workpiece hot enough to cause discoloration or to change the microstructure by tempering or hardening.

Finally, consider the machine tool, toolholder and spindle interface. Rigidity across the board is needed for productive titanium machining. WIDIA offers the KM4X platform, which according to Global Product Manager Bill Redman is “the strongest connection available, period,” and is available on a wide variety of toolholders and machine tools alike. Says Sperhake, “From Tier 1 aerospace suppliers to the job shop on the corner, everyone wants the same things from a tooling solution: higher accuracy, better surface finish, reliability and productivity. All are critical factors to their success, and that’s what we intend to deliver. WS40PM is a big part of that.”

WS40PM was designed to meet the needs of the aerospace, defense, and medical industries, where titanium is used for everything from landing gear and seat tracks to lifesaving implants and surgical instruments. As the testing results show, however, WS40PM is suitable for far more than titanium. High-temp steel alloys, austenitic and PH stainless steels, nickel-based superalloys such as Hastelloy and Nitronic—these materials cause tool failure due to built-up edge (BUE), notching at the depth of cut line, cratering, chipping and extreme heat generation, which in the case of wet-cutting operations lead to cracking.

Sperhake recommends a balanced approach to cutting parameter selection. “As radial engagement increases, cutting speeds should be reduced proportionately,” he says. “That’s because the amount of heat entering the insert goes up substantially on heavy cuts. At around 90 percent engagement, for instance, you’ll probably want to reduce the RPM by 25 percent or so, depending on the material. Feed rates may also have to be lessened somewhat, depending on setup and machine rigidity. And smaller cut widths, of course, spindle speed and feed rates should be kicked up substantially.” “Going too easy” is a common mistake when machining titanium and other difficult materials, Sperhake says, leading to poor productivity levels and shortened tool life. For example, problems such as BUE and edge wear can often be eliminated by pushing the tool harder. “Tool life, especially in superalloys, is a three-legged stool of feed, speed and cutter engagement. Each has a direct impact on the others.”

Runs endmills and arbor-mounted milling cutters. Features include a head with a spindle that drives the cutters; a column, knee and table that provide motion in the three Cartesian axes; and a base that supports the components and houses the cutting-fluid pump and reservoir. The work is mounted on the table and fed into the rotating cutter or endmill to accomplish the milling steps; vertical milling machines also feed endmills into the work by means of a spindle-mounted quill. Models range from small manual machines to big bed-type and duplex mills. All take one of three basic forms: vertical, horizontal or convertible horizontal/vertical. Vertical machines may be knee-type (the table is mounted on a knee that can be elevated) or bed-type (the table is securely supported and only moves horizontally). In general, horizontal machines are bigger and more powerful, while vertical machines are lighter but more versatile and easier to set up and operate.

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

Liquid used to improve workpiece machinability, enhance tool life, flush out chips and machining debris, and cool the workpiece and tool. Three basic types are: straight oils; soluble oils, which emulsify in water; and synthetic fluids, which are water-based chemical solutions having no oil. See coolant; semisynthetic cutting fluid; soluble-oil cutting fluid; synthetic cutting fluid.

Distance between the bottom of the cut and the uncut surface of the workpiece, measured in a direction at right angles to the machined surface of the workpiece.

Fluid that reduces temperature buildup at the tool/workpiece interface during machining. Normally takes the form of a liquid such as soluble or chemical mixtures (semisynthetic, synthetic) but can be pressurized air or other gas. Because of water’s ability to absorb great quantities of heat, it is widely used as a coolant and vehicle for various cutting compounds, with the water-to-compound ratio varying with the machining task. See cutting fluid; semisynthetic cutting fluid; soluble-oil cutting fluid; synthetic cutting fluid.

Substances having metallic properties and being composed of two or more chemical elements of which at least one is a metal.

Tool-coating process performed at low temperature (500° C), compared to chemical vapor deposition (1,000° C). Employs electric field to generate necessary heat for depositing coating on a tool’s surface. See CVD, chemical vapor deposition.

In each instance, WS40PM competed with the test subject’s legacy carbide grade. Speeds and feeds were kept the same or in some cases increased to take advantage of WS40PM’s exceptional toughness, wear-resistance and ability to resist thermal cracking.

Success with superalloys takes more than a good carbide grade, however. Sperhake also recommends increasing the cutting fluid concentration, and using a high-pressure coolant pump wherever possible. Selecting the right cutter body for the application is likewise important. WIDIA’s VSM490 shoulder mill offers a state of the art insert and cutter design, one that supports WS40PM and other high-performance grades.

Tangential velocity on the surface of the tool or workpiece at the cutting interface. The formula for cutting speed (sfm) is tool diameter 5 0.26 5 spindle speed (rpm). The formula for feed per tooth (fpt) is table feed (ipm)/number of flutes/spindle speed (rpm). The formula for spindle speed (rpm) is cutting speed (sfm) 5 3.82/tool diameter. The formula for table feed (ipm) is feed per tooth (ftp) 5 number of tool flutes 5 spindle speed (rpm).

Josef Fellner, WIDIA Products Group’s manager portfolio management for turning and indexable milling, says the company recently took its newest advanced milling grade, WS40PM, on a world-wide testing tour. The results have been quite impressive: ♦ An aircraft manufacturer enjoyed a 90 percent reduction in machining time per piece and increased tool life by 50 percent during Ti-6Al-4V face milling operations. ♦ Insert flank wear decreased by more than 90 percent at a UK shop cutting Inconel 625, resulting in a 70 percent reduction in tooling costs. ♦ At a turbocharger producer in China, tool life increased 80 percent while machining an austenitic stainless steel component using WS40PM, with improved part surface quality, reduced cutting forces and better chip flow. ♦ In another titanium component, the WS40PM/VSM490-15 platform doubled metal-removal rates and delivered 80 percent longer tool life through increased depth of cut and feed per tooth in face and shoulder milling operations. ♦ The testing laboratory for a well-known brand of machine tools reports metal-removal rates 49 percent greater when shoulder milling Ti-6Al-4V.

Phenomenon leading to fracture under repeated or fluctuating stresses having a maximum value less than the tensile strength of the material. Fatigue fractures are progressive, beginning as minute cracks that grow under the action of the fluctuating stress.

1. Permanently damaging a metal by heating to cause either incipient melting or intergranular oxidation. 2. In grinding, getting the workpiece hot enough to cause discoloration or to change the microstructure by tempering or hardening.

18581906093

18581906093