Carbide Insert Turning Tools - carbide cutting inserts

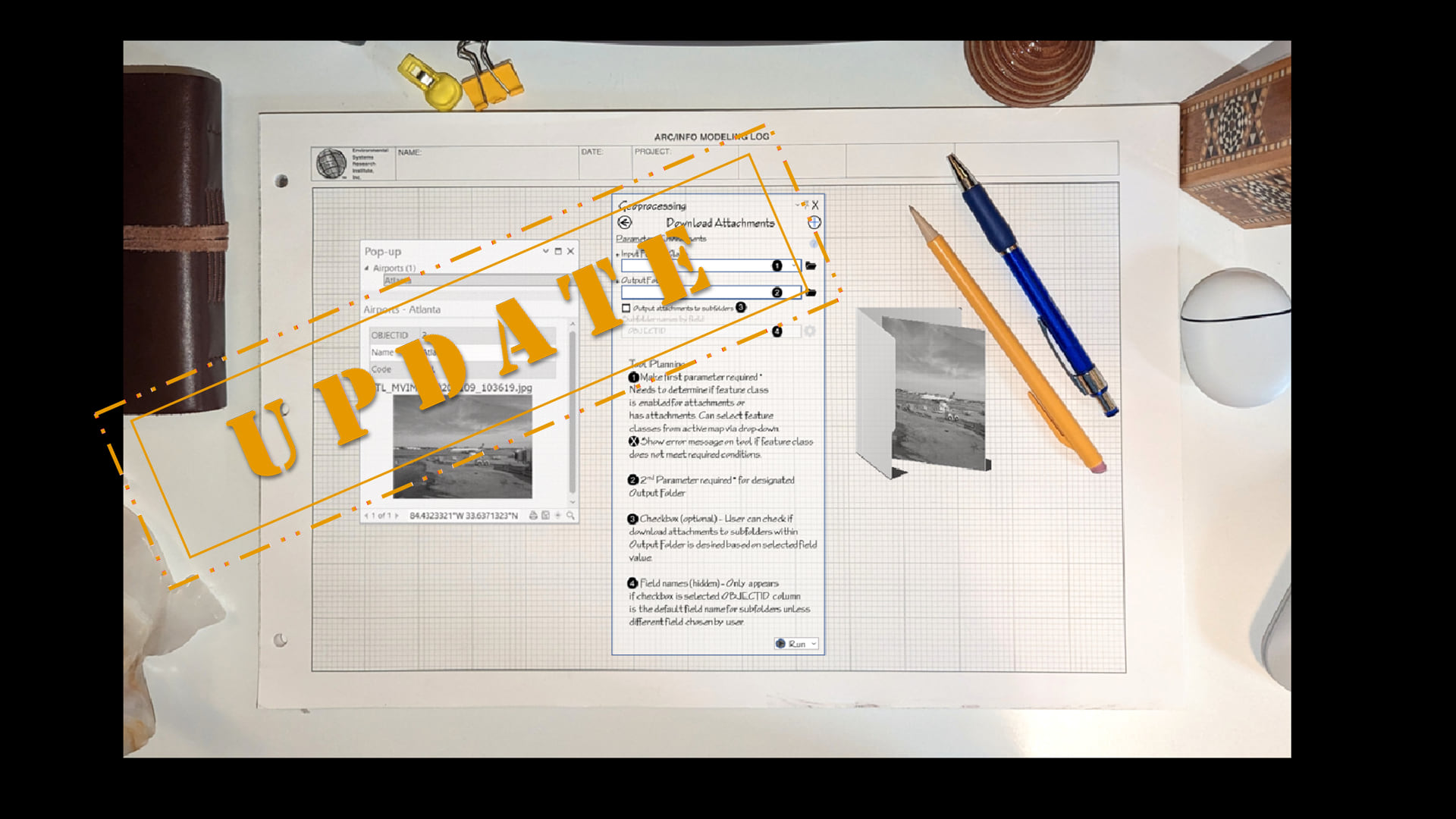

d. Subfolder names by field—The fourth parameter is dependent on the third parameter and will only display if the optional check box is checked. If it’s checked, the user can then select a field from the feature class for the sub-folder names. (The validation script implements this behavior on the tool, which will also be available for review in a copy of the final tool).

All concrete general names are connotative. The word man, for example, denotes Peter, Jane, John, and an indefinite number of other individuals, of whom, taken as a class, it is the name. But it is applied to them, because they possess, and to signify that they possess, certain attributes. These seem to be, corporeity, animal life, rationality, and a certain external form, which for distinction we call the human. Every existing thing, which possessed all these attributes, would be called a man; and anything which possessed none of them, or only one, or two, or even three of them without the fourth, would not be so called. For example, if in the interior of Africa there were to be discovered a race of animals possessing reason equal to that of human beings, but with the form of an elephant, they would not be called men. Swift's Houyhnhnms would not be so called. Or if such newly-discovered beings possessed the form of man without any vestige of reason, it is probable that some other name than that of man would be found for them. How it happens that there can be any doubt about the matter, will appear hereafter. The word man, therefore, signifies all these attributes, and all subjects which possess these attributes. But it can be predicated only of the subjects. What we call men, are the subjects, the individual Stiles and Nokes; not the qualities by which their humanity is constituted. The name, therefore, is said to signify the subjects directly, the attributes indirectly; it denotes the subjects, and implies, or involves, or indicates, or as we shall say henceforth connotes the attributes. It is a connotative name. Connotative names [N1] have hence been also called denominative, because the subject which they denote is denominated by, or receives a name from, the attribute which they connote. Snow, and other objects, receive the name white, because they possess the attribute which is called whiteness; Peter, James and others receive the name man because they possess the attributes which are considered to constitute humanity. The attribute, or attribute, may therefore be said to denominate those objects, or to give them a common name. It has been seen that all concrete general names are connotative. Even abstract names, though the names only of attributes, may in some instances be justly considered connotative; for attributes themselves may have attributes ascribed to them; and a word which denotes attributes may connote an attribute of those attributes. Of this description, for example, is such a word as fault; equivalent to a bad or hurtful quality. This word is a name common to many attributes, and connotes hurtfulness, an attribute of those various attributes. When, for example, we say that slowness in a horse is a fault, we do not mean that the slow movement, the actual change of placed of the slow horse, is a bad thing, but that the property or peculiarity of the horse, from which it derives that name, the quality of being a slow mover, is an undesirable peculiarity. In regard to those concrete names which are not general but individual, a distinction must be made. Proper names are not connotative: they denote the individuals who are called by them; but they do not indicate or imply any attributes as belonging to those individuals. When we name a child by the name Paul, or a dog by the name Caesar, these names are simply marks used to enable those individuals to be made subjects of discourse. It may be said, indeed, that we must have had some reason for giving them those names rather than others; and that is true; but the name, once given, is independent of the reason. I man may have been named John, because that was the name of his father; a town may have been named Dartmouth, because it is situated at the mouth of the Dart. But it is no part of the signification of the word John, that. the father of the person so called bore the same name; nor even of the word Dartmouth, to be situated at the mouth of the Dart. If sand should choke up the mouth of the river, or an earthquake change its course, and remove it to a distance from the town, the name of the town would not necessarily be changed. That fact, therefore, can form no part of the signification of the word; for otherwise, when the fact confessedly ceased to be true, no one would any longer think of applying the name. Proper names are attached to the objects themselves, and are not dependent on the continuance of any attribute of the object. But there is another kind of names, which, although they are individual names, that is, predicable only of one object, are really connotative. For, though we may give to an individual a name utterly unmeaning, which we call a proper name, - a word which answers the purpose of showing what thing it is we are talking about, but not of telling anything about it; yet a name peculiar to an individual is not necessarily of this description. It may be significant of some attribute, or some union of attributes, which, being possessed by no object but one, determines the name exclusively to that individual. 'The sun' is a name of this description; 'God', when used by a monotheist, is another. These, however, are scarcely examples of what we are now attempting to illustrate, being, in strictness of language, general, not individual names: for, however they may be in fact predicable only of one object, there is nothing in the meaning of the words themselves which implies this: and accordingly, when we are imagining and not affirming, we may speak of many suns; and the majority of mankind have believed, and still believe, that there are many gods. But it is easy to produce words which are real instances of connotative individual names. It may be part of the meaning of the connotative name itself, that there can exist but one individual possessing the attribute which it connotes: as, for instance, 'the only son of John Stiles'; 'the first emperor of Rome'. Or the attribute connoted may be a connexion with some determinate event, and the connexion may be of such a kind as only one individual could have; or may at least be such as only one individual actually had; and this may be implied in the form of the expression. 'The father of Socrates' is an example of the one kind (since Socrates could have had two fathers); 'the author of the Iliad', 'the murderer of Henri Quatre' of the second. For, though it is conceivable that more persons than one might have participated in the authorship of the Iliad, or in the murder of Henri Quatre, the employment of the article the[E1] implies that, in fact, this was not the case. What is here done by the word the, is done in other cases by the context: thus, 'Caesar's army' is an individual name, if it appears from the context that the army meant is that which Caesar commanded in a particular battle. The still more general expressions, 'the Roman army', or 'the Christian army' may be individualised in a similar manner. Another case of frequent occurrence has already been noticed; it is the following. The name, being a many-worded one, may consist, in the first place, of a general name, capable of being affirmed of more things than one, but which is, in the second place, so limited be other words joined with it, that the entire expression can only be predicated of one object, consistently with the meaning of the general term. This is exemplified in such an instance as the following: 'the present Prime Minister of England'. Prime Minister of England is a general name; the attributes which it connotes may be possessed by an indefinite number of persons: in succession however, not simultaneously; since the meaning of the name itself imports (among other things) that there can be only one such person at a time. This being the case, and the application of the name being afterwards limited by the article and the word present, to such individuals as possess the attribute at one indivisible point of time, it becomes applicable only to one individual. And as this appears from the meaning of the name, without any extrinsic proof, it is strictly an individual name. From the preceding observations it will easily be collected, that whenever the names given to objects convey any information, that is, whenever they have properly any meaning, the meaning resides not in what they denote but in what they connote. The only names of objects which connote nothing are proper names; and these have properly speaking, no signification. If like the robber in the Arabian Nights we make a mark with chalk on a house to enable us to know it again, the mark has a purpose, but it has not properly any meaning. The chalk does not declare anything about the house; it does not mean, This is such a persons house, or This is a house which contains a booty. The object of making the mark is merely distinction. I say to myself, All these houses are so nearly alike that if I lose sight of them I shall not again be able to distinguish that which I am now looking at, from any of the others; I must therefore contrive to make the appearance of this house unlike that of others, that I may hereafter know when I see the mark not indeed any attribute of the house but simply that it is the same house that I am looking at. Morgiana chalked all the other houses in a similar manner, and defeated the scheme: how? simply by obliterating the difference of appearance between that house and the others. The chalk was still there, but it no longer served the purpose of a distinctive mark. When we impose a proper name, we perform an operation in some degree analogous to what the robber intended in chalking the house. We put a mark, not indeed upon the object itself, but, so to speak, upon the idea of the object. A proper name is but an unmeaning mark which we connect in our mind with the idea of the object in order that whenever the mark meets our eyes or occurs to our thoughts, we may think of that individual object. Not being attached to the thing itself, it does not, like the chalk, enable us to distinguish the object when we see it, but it enables us to distinguish it when it is spoken of, either in the records of our own experience, or in the discourse of others; to know that what we find asserted in any proposition of which it is the subject, is asserted of the individual thing with which we were previously acquainted. When we predicate of anything its proper name; when we say, pointing to a man, this is Brown or Smith, or pointing to a city, that it is York, we do not, merely by so doing, convey to the reader any information about them, except that those are their names. By enabling him to identify the individuals, we may connect them with information previously possessed by him; by saying this is York, we may tell him that it contains the Minster. But this is in virtue of what he has previously heard concerning York; not anything implied in the name. It is otherwise when objects are spoken of by connotative names. When we say, The town is built of marble, we give the hearer what may be entirely new information, and this merely by the signification of the many-worded connotative name 'built of marble'. Such names are not signs of the mere objects, invented because we have occasion to think and speak of those objects individually; but signs which accompany an attribute: a kind of livery in which the attribute clotes all objects which are recognised as possessing it. They are not mere marks, but more, that is to say, significant marks; and the connotation is what constitutes their significance. [N1] Archbishop Whately, who, in the later editions of his Elements of Logic, aided in reviving the important distinction treated of in the text, proposes the term 'Attributive' as a substitute for 'Connotative' (p. 22, 9th edition). The expression is, in itself, appropriate; but as it has not the advantage of being connected with any verb, of so markedly distinctive a character as 'to connote', it is not, I think, fitted to supply the place of the word Connotative in scientific use. THE LOGIC MUSEUM Copyright © E.D.Buckner 2006.

If like the robber in the Arabian Nights we make a mark with chalk on a house to enable us to know it again, the mark has a purpose, but it has not properly any meaning. The chalk does not declare anything about the house; it does not mean, This is such a persons house, or This is a house which contains a booty. The object of making the mark is merely distinction. I say to myself, All these houses are so nearly alike that if I lose sight of them I shall not again be able to distinguish that which I am now looking at, from any of the others; I must therefore contrive to make the appearance of this house unlike that of others, that I may hereafter know when I see the mark not indeed any attribute of the house but simply that it is the same house that I am looking at. Morgiana chalked all the other houses in a similar manner, and defeated the scheme: how? simply by obliterating the difference of appearance between that house and the others. The chalk was still there, but it no longer served the purpose of a distinctive mark. When we impose a proper name, we perform an operation in some degree analogous to what the robber intended in chalking the house. We put a mark, not indeed upon the object itself, but, so to speak, upon the idea of the object. A proper name is but an unmeaning mark which we connect in our mind with the idea of the object in order that whenever the mark meets our eyes or occurs to our thoughts, we may think of that individual object. Not being attached to the thing itself, it does not, like the chalk, enable us to distinguish the object when we see it, but it enables us to distinguish it when it is spoken of, either in the records of our own experience, or in the discourse of others; to know that what we find asserted in any proposition of which it is the subject, is asserted of the individual thing with which we were previously acquainted. When we predicate of anything its proper name; when we say, pointing to a man, this is Brown or Smith, or pointing to a city, that it is York, we do not, merely by so doing, convey to the reader any information about them, except that those are their names. By enabling him to identify the individuals, we may connect them with information previously possessed by him; by saying this is York, we may tell him that it contains the Minster. But this is in virtue of what he has previously heard concerning York; not anything implied in the name. It is otherwise when objects are spoken of by connotative names. When we say, The town is built of marble, we give the hearer what may be entirely new information, and this merely by the signification of the many-worded connotative name 'built of marble'. Such names are not signs of the mere objects, invented because we have occasion to think and speak of those objects individually; but signs which accompany an attribute: a kind of livery in which the attribute clotes all objects which are recognised as possessing it. They are not mere marks, but more, that is to say, significant marks; and the connotation is what constitutes their significance. [N1] Archbishop Whately, who, in the later editions of his Elements of Logic, aided in reviving the important distinction treated of in the text, proposes the term 'Attributive' as a substitute for 'Connotative' (p. 22, 9th edition). The expression is, in itself, appropriate; but as it has not the advantage of being connected with any verb, of so markedly distinctive a character as 'to connote', it is not, I think, fitted to supply the place of the word Connotative in scientific use. THE LOGIC MUSEUM Copyright © E.D.Buckner 2006.

2. In the new script properties window, on the General tab, give the tool a name and label. The label will be the name that shows up on the tool. The name and label can be the same, but the name cannot have spaces. Provide a brief description about the tool. When a user hovers the mouse over the question mark (?) icon at the top right of the tool, the software will show a text window with the description.

you will have to calculate the feed rate and speed yourself instead of using our chart. Example using a 1/4 or 0.125 bit – Straight V Carbide Tipped Endmill ...

A non-connotative term is one which signifies a subject only, or an attribute only. A connotative term is one which denotes a subject, and implies an attribute. By a subject is here meant anything which possesses attributes. Thus John, or London, or England, are names which signify a subject only. Whiteness, length, virtue, signify an attribute only. None of these names, therefore, are connotative. But white, long, virtuous, are connotative. The word white, denotes all white things, as snow, paper, the foam of the sea, &c., and implies, or in the language of the schoolmen connotes, the attribute whiteness. The word white is not predicated of the attribute, but of the subjects, snow, &c. but when we predicate it of them, we convey the meaning that the attribute whiteness belongs to them. The same may be said of the other words above cited. Virtuous, for example, is the name of a class, which includes Socrates, Howard, the Man of Ross, and an undefinable number of individuals, past, present, and to come. These individuals, collectively and severally, can alone be said with propriety to be denoted by the word: of them alone can it properly be said to be a name. But it is a name applied to all of them in consequence of an attribute which they are supposed to possess in common, the attribute which has received the name of virtue. It is applied to all beings that are considered to possess this attribute; and to none which are not so considered. All concrete general names are connotative. The word man, for example, denotes Peter, Jane, John, and an indefinite number of other individuals, of whom, taken as a class, it is the name. But it is applied to them, because they possess, and to signify that they possess, certain attributes. These seem to be, corporeity, animal life, rationality, and a certain external form, which for distinction we call the human. Every existing thing, which possessed all these attributes, would be called a man; and anything which possessed none of them, or only one, or two, or even three of them without the fourth, would not be so called. For example, if in the interior of Africa there were to be discovered a race of animals possessing reason equal to that of human beings, but with the form of an elephant, they would not be called men. Swift's Houyhnhnms would not be so called. Or if such newly-discovered beings possessed the form of man without any vestige of reason, it is probable that some other name than that of man would be found for them. How it happens that there can be any doubt about the matter, will appear hereafter. The word man, therefore, signifies all these attributes, and all subjects which possess these attributes. But it can be predicated only of the subjects. What we call men, are the subjects, the individual Stiles and Nokes; not the qualities by which their humanity is constituted. The name, therefore, is said to signify the subjects directly, the attributes indirectly; it denotes the subjects, and implies, or involves, or indicates, or as we shall say henceforth connotes the attributes. It is a connotative name. Connotative names [N1] have hence been also called denominative, because the subject which they denote is denominated by, or receives a name from, the attribute which they connote. Snow, and other objects, receive the name white, because they possess the attribute which is called whiteness; Peter, James and others receive the name man because they possess the attributes which are considered to constitute humanity. The attribute, or attribute, may therefore be said to denominate those objects, or to give them a common name. It has been seen that all concrete general names are connotative. Even abstract names, though the names only of attributes, may in some instances be justly considered connotative; for attributes themselves may have attributes ascribed to them; and a word which denotes attributes may connote an attribute of those attributes. Of this description, for example, is such a word as fault; equivalent to a bad or hurtful quality. This word is a name common to many attributes, and connotes hurtfulness, an attribute of those various attributes. When, for example, we say that slowness in a horse is a fault, we do not mean that the slow movement, the actual change of placed of the slow horse, is a bad thing, but that the property or peculiarity of the horse, from which it derives that name, the quality of being a slow mover, is an undesirable peculiarity. In regard to those concrete names which are not general but individual, a distinction must be made. Proper names are not connotative: they denote the individuals who are called by them; but they do not indicate or imply any attributes as belonging to those individuals. When we name a child by the name Paul, or a dog by the name Caesar, these names are simply marks used to enable those individuals to be made subjects of discourse. It may be said, indeed, that we must have had some reason for giving them those names rather than others; and that is true; but the name, once given, is independent of the reason. I man may have been named John, because that was the name of his father; a town may have been named Dartmouth, because it is situated at the mouth of the Dart. But it is no part of the signification of the word John, that. the father of the person so called bore the same name; nor even of the word Dartmouth, to be situated at the mouth of the Dart. If sand should choke up the mouth of the river, or an earthquake change its course, and remove it to a distance from the town, the name of the town would not necessarily be changed. That fact, therefore, can form no part of the signification of the word; for otherwise, when the fact confessedly ceased to be true, no one would any longer think of applying the name. Proper names are attached to the objects themselves, and are not dependent on the continuance of any attribute of the object. But there is another kind of names, which, although they are individual names, that is, predicable only of one object, are really connotative. For, though we may give to an individual a name utterly unmeaning, which we call a proper name, - a word which answers the purpose of showing what thing it is we are talking about, but not of telling anything about it; yet a name peculiar to an individual is not necessarily of this description. It may be significant of some attribute, or some union of attributes, which, being possessed by no object but one, determines the name exclusively to that individual. 'The sun' is a name of this description; 'God', when used by a monotheist, is another. These, however, are scarcely examples of what we are now attempting to illustrate, being, in strictness of language, general, not individual names: for, however they may be in fact predicable only of one object, there is nothing in the meaning of the words themselves which implies this: and accordingly, when we are imagining and not affirming, we may speak of many suns; and the majority of mankind have believed, and still believe, that there are many gods. But it is easy to produce words which are real instances of connotative individual names. It may be part of the meaning of the connotative name itself, that there can exist but one individual possessing the attribute which it connotes: as, for instance, 'the only son of John Stiles'; 'the first emperor of Rome'. Or the attribute connoted may be a connexion with some determinate event, and the connexion may be of such a kind as only one individual could have; or may at least be such as only one individual actually had; and this may be implied in the form of the expression. 'The father of Socrates' is an example of the one kind (since Socrates could have had two fathers); 'the author of the Iliad', 'the murderer of Henri Quatre' of the second. For, though it is conceivable that more persons than one might have participated in the authorship of the Iliad, or in the murder of Henri Quatre, the employment of the article the[E1] implies that, in fact, this was not the case. What is here done by the word the, is done in other cases by the context: thus, 'Caesar's army' is an individual name, if it appears from the context that the army meant is that which Caesar commanded in a particular battle. The still more general expressions, 'the Roman army', or 'the Christian army' may be individualised in a similar manner. Another case of frequent occurrence has already been noticed; it is the following. The name, being a many-worded one, may consist, in the first place, of a general name, capable of being affirmed of more things than one, but which is, in the second place, so limited be other words joined with it, that the entire expression can only be predicated of one object, consistently with the meaning of the general term. This is exemplified in such an instance as the following: 'the present Prime Minister of England'. Prime Minister of England is a general name; the attributes which it connotes may be possessed by an indefinite number of persons: in succession however, not simultaneously; since the meaning of the name itself imports (among other things) that there can be only one such person at a time. This being the case, and the application of the name being afterwards limited by the article and the word present, to such individuals as possess the attribute at one indivisible point of time, it becomes applicable only to one individual. And as this appears from the meaning of the name, without any extrinsic proof, it is strictly an individual name. From the preceding observations it will easily be collected, that whenever the names given to objects convey any information, that is, whenever they have properly any meaning, the meaning resides not in what they denote but in what they connote. The only names of objects which connote nothing are proper names; and these have properly speaking, no signification. If like the robber in the Arabian Nights we make a mark with chalk on a house to enable us to know it again, the mark has a purpose, but it has not properly any meaning. The chalk does not declare anything about the house; it does not mean, This is such a persons house, or This is a house which contains a booty. The object of making the mark is merely distinction. I say to myself, All these houses are so nearly alike that if I lose sight of them I shall not again be able to distinguish that which I am now looking at, from any of the others; I must therefore contrive to make the appearance of this house unlike that of others, that I may hereafter know when I see the mark not indeed any attribute of the house but simply that it is the same house that I am looking at. Morgiana chalked all the other houses in a similar manner, and defeated the scheme: how? simply by obliterating the difference of appearance between that house and the others. The chalk was still there, but it no longer served the purpose of a distinctive mark. When we impose a proper name, we perform an operation in some degree analogous to what the robber intended in chalking the house. We put a mark, not indeed upon the object itself, but, so to speak, upon the idea of the object. A proper name is but an unmeaning mark which we connect in our mind with the idea of the object in order that whenever the mark meets our eyes or occurs to our thoughts, we may think of that individual object. Not being attached to the thing itself, it does not, like the chalk, enable us to distinguish the object when we see it, but it enables us to distinguish it when it is spoken of, either in the records of our own experience, or in the discourse of others; to know that what we find asserted in any proposition of which it is the subject, is asserted of the individual thing with which we were previously acquainted. When we predicate of anything its proper name; when we say, pointing to a man, this is Brown or Smith, or pointing to a city, that it is York, we do not, merely by so doing, convey to the reader any information about them, except that those are their names. By enabling him to identify the individuals, we may connect them with information previously possessed by him; by saying this is York, we may tell him that it contains the Minster. But this is in virtue of what he has previously heard concerning York; not anything implied in the name. It is otherwise when objects are spoken of by connotative names. When we say, The town is built of marble, we give the hearer what may be entirely new information, and this merely by the signification of the many-worded connotative name 'built of marble'. Such names are not signs of the mere objects, invented because we have occasion to think and speak of those objects individually; but signs which accompany an attribute: a kind of livery in which the attribute clotes all objects which are recognised as possessing it. They are not mere marks, but more, that is to say, significant marks; and the connotation is what constitutes their significance. [N1] Archbishop Whately, who, in the later editions of his Elements of Logic, aided in reviving the important distinction treated of in the text, proposes the term 'Attributive' as a substitute for 'Connotative' (p. 22, 9th edition). The expression is, in itself, appropriate; but as it has not the advantage of being connected with any verb, of so markedly distinctive a character as 'to connote', it is not, I think, fitted to supply the place of the word Connotative in scientific use. THE LOGIC MUSEUM Copyright © E.D.Buckner 2006.

Parting store tool lathe, Lathe Parting Tool Holder with Blade 1 16 store. ... Glanze Parting Tool Axminster Tools store, Mini Parting Tool Cut off Holder ...

RS Industry. RS Industry is a private company that was established on February 9, 2013. The aim of the company is to carry out assembly work in the field of ...

See also Aquinas' account of singular propositions in Q86 of the Summa Theologiae here, from which it is clear that the traditional theory of the proposition, while it is compositional with respect to universal terms such as 'man', 'white' and so on, is not compositional with respect to singular terms such as 'Socrates', 'Aristotle' and so on.

In conclusion, I hope that this sample script and script tool provide some functionality that can be useful in your current or future workflows. I always learn something new from sample scripts and demonstrations that I can apply directly to a current project or later use. While this tool is all about downloading attachments from a feature class, you might find it to be more helpful for automating other workflows, better understanding of the Describe function or tool behavior. Either way, have fun and good luck creating your own data management geoprocessing tool to download attachments. Feel free to edit, update, improve or customize for your individual or organizational needs!

Surprisingly, it has not been available on the internet before now. This version is taken from the eighth edition. A number of misconceptions surround what Mill says in this chapter. First, there is the common confusion between the antitheses of sense and reference, and connotation and denotation. These are not the same. The distinction between sense and reference was an idea of the German logician Gottlob Frege (1848-1925), whereas the idea of 'denotation' belongs to the traditional logic of which Mill's book was one of the last great works, and which Frege's system superseded. Thus Mill says that 'the word white, denotes all white things, as snow, paper'. In Frege's system, and all subsequent systems, we would not say that a common noun, which is logically a predicate, can refer to anything. (For Frege, a common noun does have a reference, but this is not the object to which the term applies, such as a man, a horse, a table &c, but an abstract thing he called a Concept or Begriff). Mill's distinction between Connotation and Denotation is much closer to that between Concept and Object, than to that between 'sense' and 'reference'. Second, Mill's theory of proper names is not really 'Millian' at all. The contemporary 'Millian' or 'direct reference' theory is that a proper name 'has no meaning but its bearer or referent' (see for example William Lycan's website here). So, on the theory of direct reference, proper names do have a meaning. On Mill's theory (and in traditional theories in general) proper names have no meaning at all. Note Mill's remarks that proper names 'properly speaking, no signification', also the passage about the robber in the Arabian nights , for an explanation of this. Third, the 'Millian' theory did not originate with Mill at all, but is much older. You can find it in Reid, for example: From what has been said of logical definition, it is evident, that no word can be logically defined which does not denote a species; because such things only can have a specific difference; and a specific difference is essential to a logical definition. On this account there can be no logical definition of individual things, such as London or Paris. Individuals are distinguished either by proper names, or by accidental circumstances of time or place; but they have no specific difference; and, therefore, though they may be known by proper names, or may be described by circumstances or relations, they cannot be defined. [Reid pp 219-20] See also Aquinas' account of singular propositions in Q86 of the Summa Theologiae here, from which it is clear that the traditional theory of the proposition, while it is compositional with respect to universal terms such as 'man', 'white' and so on, is not compositional with respect to singular terms such as 'Socrates', 'Aristotle' and so on. References Reid, T., ed. Hamilton, The Works of Thomas Reid, Edinburgh 1846 Section §5 of Book I, Chapter i of System of Logic, by John Stuart Mill §5. This leads to the consideration of a third great division of names, into connotative and non-connotative, the latter sometimes, but improperly, called absolute. This is one of the most important distinctions which we shall have occasion to point out, and one of those which go deepest into the nature of language. A non-connotative term is one which signifies a subject only, or an attribute only. A connotative term is one which denotes a subject, and implies an attribute. By a subject is here meant anything which possesses attributes. Thus John, or London, or England, are names which signify a subject only. Whiteness, length, virtue, signify an attribute only. None of these names, therefore, are connotative. But white, long, virtuous, are connotative. The word white, denotes all white things, as snow, paper, the foam of the sea, &c., and implies, or in the language of the schoolmen connotes, the attribute whiteness. The word white is not predicated of the attribute, but of the subjects, snow, &c. but when we predicate it of them, we convey the meaning that the attribute whiteness belongs to them. The same may be said of the other words above cited. Virtuous, for example, is the name of a class, which includes Socrates, Howard, the Man of Ross, and an undefinable number of individuals, past, present, and to come. These individuals, collectively and severally, can alone be said with propriety to be denoted by the word: of them alone can it properly be said to be a name. But it is a name applied to all of them in consequence of an attribute which they are supposed to possess in common, the attribute which has received the name of virtue. It is applied to all beings that are considered to possess this attribute; and to none which are not so considered. All concrete general names are connotative. The word man, for example, denotes Peter, Jane, John, and an indefinite number of other individuals, of whom, taken as a class, it is the name. But it is applied to them, because they possess, and to signify that they possess, certain attributes. These seem to be, corporeity, animal life, rationality, and a certain external form, which for distinction we call the human. Every existing thing, which possessed all these attributes, would be called a man; and anything which possessed none of them, or only one, or two, or even three of them without the fourth, would not be so called. For example, if in the interior of Africa there were to be discovered a race of animals possessing reason equal to that of human beings, but with the form of an elephant, they would not be called men. Swift's Houyhnhnms would not be so called. Or if such newly-discovered beings possessed the form of man without any vestige of reason, it is probable that some other name than that of man would be found for them. How it happens that there can be any doubt about the matter, will appear hereafter. The word man, therefore, signifies all these attributes, and all subjects which possess these attributes. But it can be predicated only of the subjects. What we call men, are the subjects, the individual Stiles and Nokes; not the qualities by which their humanity is constituted. The name, therefore, is said to signify the subjects directly, the attributes indirectly; it denotes the subjects, and implies, or involves, or indicates, or as we shall say henceforth connotes the attributes. It is a connotative name. Connotative names [N1] have hence been also called denominative, because the subject which they denote is denominated by, or receives a name from, the attribute which they connote. Snow, and other objects, receive the name white, because they possess the attribute which is called whiteness; Peter, James and others receive the name man because they possess the attributes which are considered to constitute humanity. The attribute, or attribute, may therefore be said to denominate those objects, or to give them a common name. It has been seen that all concrete general names are connotative. Even abstract names, though the names only of attributes, may in some instances be justly considered connotative; for attributes themselves may have attributes ascribed to them; and a word which denotes attributes may connote an attribute of those attributes. Of this description, for example, is such a word as fault; equivalent to a bad or hurtful quality. This word is a name common to many attributes, and connotes hurtfulness, an attribute of those various attributes. When, for example, we say that slowness in a horse is a fault, we do not mean that the slow movement, the actual change of placed of the slow horse, is a bad thing, but that the property or peculiarity of the horse, from which it derives that name, the quality of being a slow mover, is an undesirable peculiarity. In regard to those concrete names which are not general but individual, a distinction must be made. Proper names are not connotative: they denote the individuals who are called by them; but they do not indicate or imply any attributes as belonging to those individuals. When we name a child by the name Paul, or a dog by the name Caesar, these names are simply marks used to enable those individuals to be made subjects of discourse. It may be said, indeed, that we must have had some reason for giving them those names rather than others; and that is true; but the name, once given, is independent of the reason. I man may have been named John, because that was the name of his father; a town may have been named Dartmouth, because it is situated at the mouth of the Dart. But it is no part of the signification of the word John, that. the father of the person so called bore the same name; nor even of the word Dartmouth, to be situated at the mouth of the Dart. If sand should choke up the mouth of the river, or an earthquake change its course, and remove it to a distance from the town, the name of the town would not necessarily be changed. That fact, therefore, can form no part of the signification of the word; for otherwise, when the fact confessedly ceased to be true, no one would any longer think of applying the name. Proper names are attached to the objects themselves, and are not dependent on the continuance of any attribute of the object. But there is another kind of names, which, although they are individual names, that is, predicable only of one object, are really connotative. For, though we may give to an individual a name utterly unmeaning, which we call a proper name, - a word which answers the purpose of showing what thing it is we are talking about, but not of telling anything about it; yet a name peculiar to an individual is not necessarily of this description. It may be significant of some attribute, or some union of attributes, which, being possessed by no object but one, determines the name exclusively to that individual. 'The sun' is a name of this description; 'God', when used by a monotheist, is another. These, however, are scarcely examples of what we are now attempting to illustrate, being, in strictness of language, general, not individual names: for, however they may be in fact predicable only of one object, there is nothing in the meaning of the words themselves which implies this: and accordingly, when we are imagining and not affirming, we may speak of many suns; and the majority of mankind have believed, and still believe, that there are many gods. But it is easy to produce words which are real instances of connotative individual names. It may be part of the meaning of the connotative name itself, that there can exist but one individual possessing the attribute which it connotes: as, for instance, 'the only son of John Stiles'; 'the first emperor of Rome'. Or the attribute connoted may be a connexion with some determinate event, and the connexion may be of such a kind as only one individual could have; or may at least be such as only one individual actually had; and this may be implied in the form of the expression. 'The father of Socrates' is an example of the one kind (since Socrates could have had two fathers); 'the author of the Iliad', 'the murderer of Henri Quatre' of the second. For, though it is conceivable that more persons than one might have participated in the authorship of the Iliad, or in the murder of Henri Quatre, the employment of the article the[E1] implies that, in fact, this was not the case. What is here done by the word the, is done in other cases by the context: thus, 'Caesar's army' is an individual name, if it appears from the context that the army meant is that which Caesar commanded in a particular battle. The still more general expressions, 'the Roman army', or 'the Christian army' may be individualised in a similar manner. Another case of frequent occurrence has already been noticed; it is the following. The name, being a many-worded one, may consist, in the first place, of a general name, capable of being affirmed of more things than one, but which is, in the second place, so limited be other words joined with it, that the entire expression can only be predicated of one object, consistently with the meaning of the general term. This is exemplified in such an instance as the following: 'the present Prime Minister of England'. Prime Minister of England is a general name; the attributes which it connotes may be possessed by an indefinite number of persons: in succession however, not simultaneously; since the meaning of the name itself imports (among other things) that there can be only one such person at a time. This being the case, and the application of the name being afterwards limited by the article and the word present, to such individuals as possess the attribute at one indivisible point of time, it becomes applicable only to one individual. And as this appears from the meaning of the name, without any extrinsic proof, it is strictly an individual name. From the preceding observations it will easily be collected, that whenever the names given to objects convey any information, that is, whenever they have properly any meaning, the meaning resides not in what they denote but in what they connote. The only names of objects which connote nothing are proper names; and these have properly speaking, no signification. If like the robber in the Arabian Nights we make a mark with chalk on a house to enable us to know it again, the mark has a purpose, but it has not properly any meaning. The chalk does not declare anything about the house; it does not mean, This is such a persons house, or This is a house which contains a booty. The object of making the mark is merely distinction. I say to myself, All these houses are so nearly alike that if I lose sight of them I shall not again be able to distinguish that which I am now looking at, from any of the others; I must therefore contrive to make the appearance of this house unlike that of others, that I may hereafter know when I see the mark not indeed any attribute of the house but simply that it is the same house that I am looking at. Morgiana chalked all the other houses in a similar manner, and defeated the scheme: how? simply by obliterating the difference of appearance between that house and the others. The chalk was still there, but it no longer served the purpose of a distinctive mark. When we impose a proper name, we perform an operation in some degree analogous to what the robber intended in chalking the house. We put a mark, not indeed upon the object itself, but, so to speak, upon the idea of the object. A proper name is but an unmeaning mark which we connect in our mind with the idea of the object in order that whenever the mark meets our eyes or occurs to our thoughts, we may think of that individual object. Not being attached to the thing itself, it does not, like the chalk, enable us to distinguish the object when we see it, but it enables us to distinguish it when it is spoken of, either in the records of our own experience, or in the discourse of others; to know that what we find asserted in any proposition of which it is the subject, is asserted of the individual thing with which we were previously acquainted. When we predicate of anything its proper name; when we say, pointing to a man, this is Brown or Smith, or pointing to a city, that it is York, we do not, merely by so doing, convey to the reader any information about them, except that those are their names. By enabling him to identify the individuals, we may connect them with information previously possessed by him; by saying this is York, we may tell him that it contains the Minster. But this is in virtue of what he has previously heard concerning York; not anything implied in the name. It is otherwise when objects are spoken of by connotative names. When we say, The town is built of marble, we give the hearer what may be entirely new information, and this merely by the signification of the many-worded connotative name 'built of marble'. Such names are not signs of the mere objects, invented because we have occasion to think and speak of those objects individually; but signs which accompany an attribute: a kind of livery in which the attribute clotes all objects which are recognised as possessing it. They are not mere marks, but more, that is to say, significant marks; and the connotation is what constitutes their significance. [N1] Archbishop Whately, who, in the later editions of his Elements of Logic, aided in reviving the important distinction treated of in the text, proposes the term 'Attributive' as a substitute for 'Connotative' (p. 22, 9th edition). The expression is, in itself, appropriate; but as it has not the advantage of being connected with any verb, of so markedly distinctive a character as 'to connote', it is not, I think, fitted to supply the place of the word Connotative in scientific use. THE LOGIC MUSEUM Copyright © E.D.Buckner 2006.

When we predicate of anything its proper name; when we say, pointing to a man, this is Brown or Smith, or pointing to a city, that it is York, we do not, merely by so doing, convey to the reader any information about them, except that those are their names. By enabling him to identify the individuals, we may connect them with information previously possessed by him; by saying this is York, we may tell him that it contains the Minster. But this is in virtue of what he has previously heard concerning York; not anything implied in the name. It is otherwise when objects are spoken of by connotative names. When we say, The town is built of marble, we give the hearer what may be entirely new information, and this merely by the signification of the many-worded connotative name 'built of marble'. Such names are not signs of the mere objects, invented because we have occasion to think and speak of those objects individually; but signs which accompany an attribute: a kind of livery in which the attribute clotes all objects which are recognised as possessing it. They are not mere marks, but more, that is to say, significant marks; and the connotation is what constitutes their significance. [N1] Archbishop Whately, who, in the later editions of his Elements of Logic, aided in reviving the important distinction treated of in the text, proposes the term 'Attributive' as a substitute for 'Connotative' (p. 22, 9th edition). The expression is, in itself, appropriate; but as it has not the advantage of being connected with any verb, of so markedly distinctive a character as 'to connote', it is not, I think, fitted to supply the place of the word Connotative in scientific use. THE LOGIC MUSEUM Copyright © E.D.Buckner 2006.

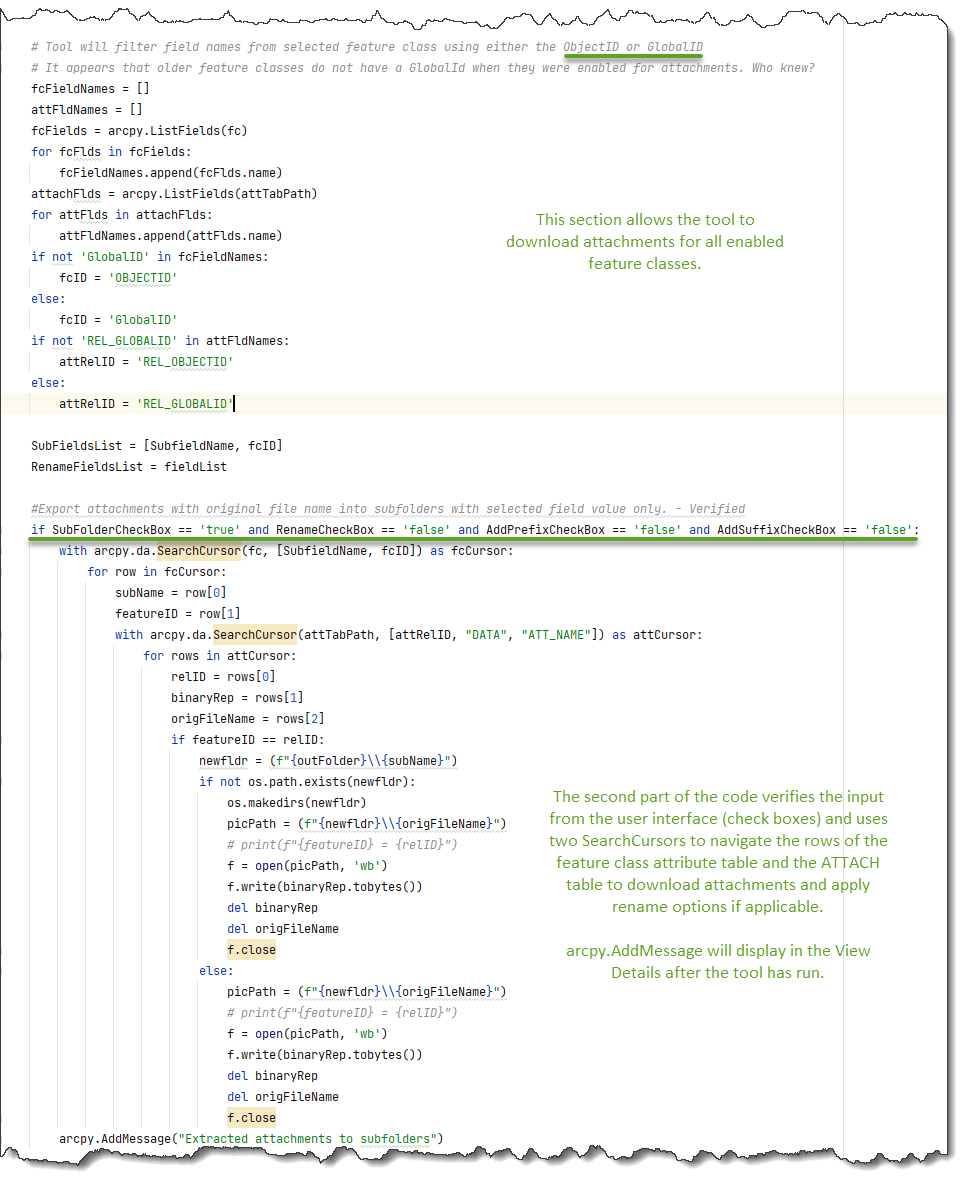

The second portion of the script verifies if the user wants to export the attachments to subfolders or rename them. Depending on the combination of options the end user chooses most of the code is similar within a series of elif statements. One important item to note. It is possible that a feature class that has been enabled for attachments may use either the OBJECTID with the REL_OBJECTID relationship in the ATTACH table, or GLOBALID’s for feature classes enabled in newer versions of the software. The script needs to check both so that all enabled feature classes work with the tool. This means that the tool should work with any enabled attachment feature class. Checkbox false on all options will download all attachments with their original names to the output folder only.

Notice that each parameter in the tool properties has a number on the left side, starting with zero. If you are thinking those are index numbers, you are correct. You will match each parameters index with updated variables in your script. The script will now use user input values instead of hard-coded values when the user clicks Run.

After years of teaching instructor-led classes and covering courses for geodatabases and Python automation, I was excited to recently join the geodatabase team to share new ways to assist our users with their workflows and projects. I know that students love examples, especially sample code and demonstrations when it comes to automating manual workflows with Python scripting.

b. Output Folder—The second parameter is a required output to choose a folder to store the downloaded attachments or sub-folders with attachments if applicable.

Tip: You can add a parameter description by updating the metadata. This allows a user to mouse-over the left side of each parameter to see descriptive information, also known as a tool tip. Right click on the script tool and select Edit Metadata. Under the Syntax Section select the down arrow of the parameter to update it’s description in the Dialog Explanation text box. When finished, click Save on the Metadata Ribbon.

Additionally, check out these other helpful resources when working with attachments, geodata, Python, and custom script tools:

The Micronic tube with internal thread features a single turn thread for easy opening and closing of the tube.

f. Select Fields – This parameter will only appear if the checkbox for the Rename Output Filenames Boolean value equals true (checked). The script allows up to five field selections for renaming the exported files. The script tool validation script prevents date field selections, as the date data type was causing errors with renaming the files. If you would like to use the values from a date field, create a new text field and copy the dates to the new text field. Be aware that special characters such as slashes (“/”) or colons and semicolons (“:”, “;”) will likely cause an operating system error when attempting to rename files or sub-folders. Consider replacing special characters with spaces, underscores or hyphens.

A Universe of Metal Sculpture: Written by Harvey Henry, 2010 Edition, Publisher: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. [Hardcover]: Books - Amazon.ca.

g. Keep existing filename and add field value as a prefix to filename – This optional parameter adds selected field values with an underscore to the beginning of the original filename.

The following static code snippet gives you a glimpse of how you will check to make sure the selected feature class has been enabled for attachments using the arcpy Describe function. You will also use the Describe function to return the associated ATTACH table. This table stores your attachments in the DATA column as binary large objects (BLOB data). If the ATTACH table is empty, your tool will notify the user that the selected feature class has no attachments to download with an error message.

With your script updated to gather the input from the user on the tools interface, you can save a copy of it and load the script into the tool.

e. Rename Output Filenames – This is another optional parameter, and if checked, will allow the user to rename the exported images based on selected field values in the feature class attribute table. Note: Renamed files will have an underscore inserted between the field values. When renaming exported attachments based on field values the tool automatically appends the AttachmentID number as the last value to avoid duplicate filenames.

Proper names are not connotative: they denote the individuals who are called by them; but they do not indicate or imply any attributes as belonging to those individuals. When we name a child by the name Paul, or a dog by the name Caesar, these names are simply marks used to enable those individuals to be made subjects of discourse. It may be said, indeed, that we must have had some reason for giving them those names rather than others; and that is true; but the name, once given, is independent of the reason. I man may have been named John, because that was the name of his father; a town may have been named Dartmouth, because it is situated at the mouth of the Dart. But it is no part of the signification of the word John, that. the father of the person so called bore the same name; nor even of the word Dartmouth, to be situated at the mouth of the Dart. If sand should choke up the mouth of the river, or an earthquake change its course, and remove it to a distance from the town, the name of the town would not necessarily be changed. That fact, therefore, can form no part of the signification of the word; for otherwise, when the fact confessedly ceased to be true, no one would any longer think of applying the name. Proper names are attached to the objects themselves, and are not dependent on the continuance of any attribute of the object. But there is another kind of names, which, although they are individual names, that is, predicable only of one object, are really connotative. For, though we may give to an individual a name utterly unmeaning, which we call a proper name, - a word which answers the purpose of showing what thing it is we are talking about, but not of telling anything about it; yet a name peculiar to an individual is not necessarily of this description. It may be significant of some attribute, or some union of attributes, which, being possessed by no object but one, determines the name exclusively to that individual. 'The sun' is a name of this description; 'God', when used by a monotheist, is another. These, however, are scarcely examples of what we are now attempting to illustrate, being, in strictness of language, general, not individual names: for, however they may be in fact predicable only of one object, there is nothing in the meaning of the words themselves which implies this: and accordingly, when we are imagining and not affirming, we may speak of many suns; and the majority of mankind have believed, and still believe, that there are many gods. But it is easy to produce words which are real instances of connotative individual names. It may be part of the meaning of the connotative name itself, that there can exist but one individual possessing the attribute which it connotes: as, for instance, 'the only son of John Stiles'; 'the first emperor of Rome'. Or the attribute connoted may be a connexion with some determinate event, and the connexion may be of such a kind as only one individual could have; or may at least be such as only one individual actually had; and this may be implied in the form of the expression. 'The father of Socrates' is an example of the one kind (since Socrates could have had two fathers); 'the author of the Iliad', 'the murderer of Henri Quatre' of the second. For, though it is conceivable that more persons than one might have participated in the authorship of the Iliad, or in the murder of Henri Quatre, the employment of the article the[E1] implies that, in fact, this was not the case. What is here done by the word the, is done in other cases by the context: thus, 'Caesar's army' is an individual name, if it appears from the context that the army meant is that which Caesar commanded in a particular battle. The still more general expressions, 'the Roman army', or 'the Christian army' may be individualised in a similar manner. Another case of frequent occurrence has already been noticed; it is the following. The name, being a many-worded one, may consist, in the first place, of a general name, capable of being affirmed of more things than one, but which is, in the second place, so limited be other words joined with it, that the entire expression can only be predicated of one object, consistently with the meaning of the general term. This is exemplified in such an instance as the following: 'the present Prime Minister of England'. Prime Minister of England is a general name; the attributes which it connotes may be possessed by an indefinite number of persons: in succession however, not simultaneously; since the meaning of the name itself imports (among other things) that there can be only one such person at a time. This being the case, and the application of the name being afterwards limited by the article and the word present, to such individuals as possess the attribute at one indivisible point of time, it becomes applicable only to one individual. And as this appears from the meaning of the name, without any extrinsic proof, it is strictly an individual name. From the preceding observations it will easily be collected, that whenever the names given to objects convey any information, that is, whenever they have properly any meaning, the meaning resides not in what they denote but in what they connote. The only names of objects which connote nothing are proper names; and these have properly speaking, no signification. If like the robber in the Arabian Nights we make a mark with chalk on a house to enable us to know it again, the mark has a purpose, but it has not properly any meaning. The chalk does not declare anything about the house; it does not mean, This is such a persons house, or This is a house which contains a booty. The object of making the mark is merely distinction. I say to myself, All these houses are so nearly alike that if I lose sight of them I shall not again be able to distinguish that which I am now looking at, from any of the others; I must therefore contrive to make the appearance of this house unlike that of others, that I may hereafter know when I see the mark not indeed any attribute of the house but simply that it is the same house that I am looking at. Morgiana chalked all the other houses in a similar manner, and defeated the scheme: how? simply by obliterating the difference of appearance between that house and the others. The chalk was still there, but it no longer served the purpose of a distinctive mark. When we impose a proper name, we perform an operation in some degree analogous to what the robber intended in chalking the house. We put a mark, not indeed upon the object itself, but, so to speak, upon the idea of the object. A proper name is but an unmeaning mark which we connect in our mind with the idea of the object in order that whenever the mark meets our eyes or occurs to our thoughts, we may think of that individual object. Not being attached to the thing itself, it does not, like the chalk, enable us to distinguish the object when we see it, but it enables us to distinguish it when it is spoken of, either in the records of our own experience, or in the discourse of others; to know that what we find asserted in any proposition of which it is the subject, is asserted of the individual thing with which we were previously acquainted. When we predicate of anything its proper name; when we say, pointing to a man, this is Brown or Smith, or pointing to a city, that it is York, we do not, merely by so doing, convey to the reader any information about them, except that those are their names. By enabling him to identify the individuals, we may connect them with information previously possessed by him; by saying this is York, we may tell him that it contains the Minster. But this is in virtue of what he has previously heard concerning York; not anything implied in the name. It is otherwise when objects are spoken of by connotative names. When we say, The town is built of marble, we give the hearer what may be entirely new information, and this merely by the signification of the many-worded connotative name 'built of marble'. Such names are not signs of the mere objects, invented because we have occasion to think and speak of those objects individually; but signs which accompany an attribute: a kind of livery in which the attribute clotes all objects which are recognised as possessing it. They are not mere marks, but more, that is to say, significant marks; and the connotation is what constitutes their significance. [N1] Archbishop Whately, who, in the later editions of his Elements of Logic, aided in reviving the important distinction treated of in the text, proposes the term 'Attributive' as a substitute for 'Connotative' (p. 22, 9th edition). The expression is, in itself, appropriate; but as it has not the advantage of being connected with any verb, of so markedly distinctive a character as 'to connote', it is not, I think, fitted to supply the place of the word Connotative in scientific use. THE LOGIC MUSEUM Copyright © E.D.Buckner 2006.

Drilling Jig for Making Precise Angled Holes...Safely! // Transform Your Drilling Projects! Watch on.

c. Output attachments to subfolders—The third parameter is an optional input to select a check box if the user wants to download the attachments to individual sub-folders based on a field value. Notice that the data type is Boolean. If checked (true), create sub-folders, otherwise load all files into a single output folder.

With your code completed and tested successfully, you can move on to designing your own script tool with a user-friendly interface to interact with the code. You can download a copy of the completed sample script later in this blog.

Learn how to use the features of the Download Attachments Sample tool to export feature class attachments to a designated folder with the option to rename the files.