Glockstore Pure Tungsten Guide Rod - pure tungsten guide rod

PlasticARM is implemented with PragmatIC’s 0.8-μm process using industry-standard chip implementation tools. We have developed a process design kit, a standard cell library and device/circuit simulations for this technology in order to implement the PlasticARM FlexIC. Figure 1c shows the FlexIC layout, where the Cortex-M processor, RAM and ROM are demarcated. The details of the implementation methodology can be found in the Methods.

a, GPIO toggles are shown when data are correct in all three tests. b, GPIO toggles are shown when data read from the ROM is incorrect. The simulation was run with a 20-kHz clock frequency.

The figure shows the evolution of the standard cell library from left to right. It starts with a 1-μm channel length library, and then moves to an 0.8 μm channel length with different sheet resistances. The far right panel shows the final library that is used to implement the PlasticARM FlexIC. VDD, supply voltage; VSS, ground; CONT, electrical contact between the source–drain layer and the next metal layer; VIA, electrical contact between routing layers.

The FlexLogIC technology (see Extended Data Table 2) has four routable metal layers of which only the lower two were used inside the standard cells. This left the top two metal layers free to be used for the interconnect between the standard cells, which could then be routed over the top of any neighbouring cells leading to a much-improved overall gate density of about 300 gates per mm2.

Dembo, H. et al. RFCPUs on glass and plastic substrates fabricated by TFT transfer technology. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 125–127 (IEEE, 2005).

Gupta, S., Navaraj, W.T., Lorenzelli, L. & Dahiya. R. Ultra-thin chips for high-performance flexible electronics. npj Flexible Electron. 2, 8 (2018).

Once the cell architecture was established, the next step was to determine the content of the cell library not only in terms of variety of logic functions but also the number of drive strength variants of each logic function. Because the effort involved to design, implement and characterize each standard cell is substantial, it was decided to run some trials with a small prototype library and then to expand the library as required. To evaluate the performance of this small prototype standard cell library some simple representative circuits (such as ring oscillators, counters and shift arrays) were implemented, manufactured and tested.

Harendt, C. et al. Hybrid Systems in Foil (HySiF) exploiting ultra-thin flexible chips. In 44th European Solid-State Device Research Conference (ESSDERC) 210–213 (2014).

PlasticARM is fabricated using a commercial ‘fab-in-a-box’ manufacturing line, FlexLogIC21, and its die micrograph is shown in Fig. 1d. The process uses an n-type metal-oxide TFT technology based on indium−gallium−zinc oxide (IGZO) and generates the FlexIC design on a 200-mm-diameter polyimide wafer. The IGZO TFT circuits are made using conventional semiconductor processing equipment adapted and configured to produce devices on a flexible (polyimide) substrate with a thickness of less than 30 μm. They have a channel length of 0.8 μm, and a minimum supply voltage of 3 V.

Carbide drill bits consist of metal—they’re either solid tungsten carbide or have tips covered in a tungsten carbide cement. Professionals can use carbide drill bits in many different industries due to their long life and durability. They are more durable than hardened steel bits, but not as much as diamond. As with any metal drill bit, there will always be wear and tear, dulling, and breakage. The good news is you can sharpen carbide bits to extend their lifespan. However, after performing several sharpening sessions, there won’t be any material left. To work properly, carbide tips need coolant to prevent burning and overheating. It is important to note that coolant mixed with the effluent creates a sludge that is messy and needs constant cleaning.

Our guide will help you understand the difference between diamond core bits and carbide in depth so you can find the right tool for your job.

Flexible electronics, on the other hand, does offer these desirable characteristics. Over the past two decades, flexible electronics have progressed to offer mature low-cost, thin, flexible and conformable devices, including sensors, memories, batteries, light-emitting diodes, energy harvesters, near-field communication/radio frequency identification and printed circuitry such as antennas. These are the essential electronic components to build any smart integrated electronic device. The missing piece is the flexible microprocessor. The main reason why no viable flexible microprocessor yet exists is that a relatively large number of TFTs need to be integrated on a flexible substrate in order to perform any meaningful computation. This has not previously been possible with the emerging flexible TFT technology, in which a certain level of technology maturity is required before a large-scale integration can be done.

Biggs, J., Myers, J., Kufel, J. et al. A natively flexible 32-bit Arm microprocessor. Nature 595, 532–536 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03625-w

After fabrication, PlasticARM was tested on a wafer probe station while still attached to a glass carrier. The input signals including a clock signal were generated externally with a ZC702 FPGA Evaluation Board from Xilinx. Both input and output signals were captured using a Saleae Logic Pro 16 logic analyser. Measurements were carried out at 3 V and 4.5 V, with various clock frequencies. An experiment with power supply set to 3 V and clock frequency of 20 kHz is shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. The ZC702 I/O voltage caps the inputs and outputs to 2.5 V. The measured data waveform is shown in Extended Data Fig. 4a, and matches the waveform in the RTL simulation of all three tests in Extended Data Fig. 3a. PlasticARM is fully functional up to 29 kHz at 3 V and 40 kHz at 4.5 V.

Design in n-type metal-oxide thin-film technology is facing many of the same challenges that affected the complexity and yield of the first silicon (negative channel metal–oxide–semiconductor, NMOS) technology during the 1970s and early 1980s, in particular poor noise margin, high power consumption, and large process variation (for example, Vt). The details of the fabrication methodology can be found in the Methods.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Ozer, E. et al. Binary neural network as a flexible integrated circuit for odour classification. In IEEE International Conference on Flexible and Printable Sensors and Systems (FLEPS) 1–4 (IEEE, 2020).

We envisage that PlasticARM will pioneer the development of low-cost, fully flexible smart integrated systems to enable an ‘internet of everything’ consisting of the integration of more than a trillion inanimate objects over the next decade into the digital world. Having an ultrathin, conformable, low-cost, natively flexible microprocessor for everyday objects will unravel innovations leading to a variety of research and business opportunities.

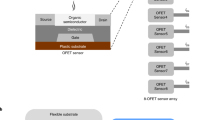

There are three major components of the natively flexible microprocessor—(1) a 32-bit CPU, (2) a 32-bit processor containing a CPU and CPU peripherals, and (3) a system-on-a-chip (SoC) containing the processor, memories and bus interfaces—all fabricated with metal-oxide TFTs on a flexible substrate. The natively flexible 32-bit processor is derived from the Arm Cortex-M0+ processor supporting the Armv6-M architecture19 (a rich set of 80+ instructions) and existing toolchain for software development (for example, compilers, debuggers, linkers, integrated development environments and so on). The entire natively flexible SoC, called PlasticARM, is capable of running programs from its internal memory. PlasticARM contains 18,334 NAND2 equivalent gates, which makes it the most complex FlexIC (at least 12× more complex than previous integrated circuits) that has been ever built with metal-oxide TFTs on a flexible substrate.

Before the implementation of the standard cell library could begin, some preliminary investigations were done to determine the most suitable standard cell architecture for the library given the constraints of the target technology. The cell architecture is the set of features that are common to every cell in the library, such as cell height, power strap sizing, routeing grid and so on, which allow the cells to be snapped together in a standard way to form larger structures. These common features are largely governed by the design rules of the manufacturing process but are also influenced by the performance and area requirements of the final design.

Ozer, E. et al. Bespoke machine learning processor development framework on flexible substrates. In IEEE International Conference on Flexible and Printable Sensors and Systems (FLEPS) 1–3 (IEEE, 2019).

Peer review information Nature thanks Zili Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

A midway approach has been to integrate silicon-based microprocessor dies onto flexible substrates—also called hybrid integration3,4,5—where the silicon wafer is thinned and dies from the wafer are integrated onto a flexible substrate. Although thin silicon die integration offers a short-term solution, the approach still relies on conventional high-cost manufacturing processes. It is, therefore, not a viable long-term solution for enabling the production of the billions of everyday smart objects expected over the next decade and beyond6.

To take full advantage of the highly automated, fast turn-around implementation and verification offered by modern silicon integrated circuit design flows, we developed a small standard cell library. A standard cell library is a collection of small pre-verified building blocks from which much larger and more complex designs can be quickly and easily built using sophisticated electronic design automation tools such as synthesis, place and route.

Ozer, E. et al. A hardwired machine learning processing engine fabricated with submicron metal-oxide thin-film transistors on a flexible substrate. Nat. Electron. 3, 419–425 (2020).

A key challenge of any resistive load technology is the power consumption. We anticipate that the lower-power cell libraries we are developing will support increased complexity, up to about 100,000 gates. Moving to more than 1,000,000 gates will probably require complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology.

Superabrasive, diamond plated tools have a major edge over carbide—longevity and cut-rate set diamond tools apart from the rest. Initially, a diamond tool will cost more money, but this investment goes toward the extended life of the bit.

IGZO TFTs are known to be bent to a radius of curvature of 3 mm without damage22, which PragmatIC has also verified through repeated bending of its own circuitry to this radius of curvature. However, all PlasticARM measurements are performed while the flexible wafer remains on its glass carrier, using standard wafer test equipment located at Arm Ltd, at room temperature. The measured results of PlasticARM are validated against its simulated results. The details of the measurement setup, results and its validation against simulation can be found in the Methods.

This dramatic reduction in both transistor and resistor size reduced the area of most cells by about 50% (see Extended Data Fig. 1), which in turn improved the manufacturing yield by bringing down the overall size of the design. However, as there were still manufacturing yield issues that we could further mitigate by changes to the standard cell architecture, the library was redrawn again. This time we focused on things that would improve the overall yield of the final design, such as the inclusion of redundant vias and contacts, reducing the number of vertices in the source–drain polygons (where possible) and keeping the size of stacked transistors to a minimum. In addition, we reverted to a lower sheet resistance in order to improve the process spread but we were able to maintain the area savings by using narrower resistors. To improve the overall quality of the logic synthesis a number of complex AND-OR-INVERT and OR-AND-INVERT logic gates were added to the library as well as some high-drive-strength simple logic gates, such as NAND2_X2 and NOR2_X2.

a, Waveform showing the functionality of PlasticARM that correctly matches the RTL simulation. b, Magnified views of GPIO input pin (I_GPIO[1]) changing from logic 0 to logic 1. c, GPIO output pin (O_GPIO[0]) changing from logic 0 to logic 1, marking an input that was held HIGH for about 1 s. The experiment was carried out with a 20-kHz clock frequency.

Early natively flexible processor works were based on developing 8-bit CPUs (refs. 9,10,11,12) using low-temperature poly-silicon TFT technology, which has a high manufacturing cost and poor lateral scalability8. Recently, two-dimensional material-based transistors have been used to develop processors such as a 1-bit CPU using molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) transistors13, and a 16-bit RISC-V CPU14 built from complementary carbon nanotube transistors. However, both works were demonstrated on a conventional silicon wafer rather than on a flexible substrate.

Growing Opportunities in the Internet of Things (McKinsey, 2019); https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-equity-and-principal-investors/our-insights/growing-opportunities-in-the-internet-of-things

J.B. and J.M. conceived the PlasticARM concept. S.C. designed the Cortex-M processor and J.B., J.M. and J.K. implemented the SoC. J.K. developed the PlasticARM test framework. A.S., C.R., K.W., R.P. and S.W. developed the fabrication process and methodology for the PlasticARM FlexIC. All authors contributed to analysis of the data generated in the development of PlasticARM. E.O., J.B., J.K., J.M., C.R., R.P. and S.W. wrote the paper.

We captured the timing characteristics of the functional PlasticARM FlexIC using a test measurement setup, and compared the measured results with the results of its register-transfer level (RTL) simulation in order to validate the functionality.

We report a fully functional PlasticARM FlexIC. This has been demonstrated by running the three test programs pre-programmed (hardwired) into the ROM before fabrication. Although the test programs are executed from the ROM, this is not a requirement for the system; it simply facilitates the test setup of PlasticARM. The current ROM implementation does not allow changing or updating of the program code after fabrication, although this would be possible in future implementations (for example, via programmable ROM). The test programs are written in such a way that the instructions exercise all functional units inside the CPU such as arithmetic logic units, load/store units and branch units, and are compiled with the armcc compiler using the CPU flag set to ‘cortex-m0plus’. The flow chart and detailed description of the test programs are shown in Fig. 2. When each test program completes its execution, the result of the test program is transmitted over the output GPIO pin off-chip to the test framework.

Process parameters and statistical variations of TFT parameters are summarized in Extended Data Table 2. FlexLogIC is a proprietary 200-mm wafer semiconductor manufacturing process that creates patterned layers of metal-oxide thin-film transistors and resistors, with four routable (gold-free) metal layers deposited onto a flexible polyimide substrate according to the FlexIC design. Repeated instances of the FlexIC design are realized by running multiple sequences of thin-film material deposition, patterning and etching. For ease of handling and to allow industry standard process tools to be used and sub-micrometre patterned features to be achieved (down to 0.8 μm), the flexible polyimide substrate is spin-coated onto glass at the outset of production. The process has been optimized to ensure that the thickness variation is substantially less than 3% over a lateral distance of 20 mm. Thin-film material deposition is achieved through a combination of physical-vapour deposition, atomic-layer deposition and solution-processing (for example, spin-coating). Substrate processing conditions have been carefully optimized to minimise film stress and substrate bow. Feature patterning is achieved using a photolithographic 5× stepper tool, which images a shot that is repeated at multiple instances across the 200-mm-diameter wafer. Each shot is focused individually, which further compensates for any thickness variation within the spun-cast film. The technology measurements were carried out using process control monitoring structures.

Nearly 50 years ago, Intel created the world’s first commercially produced microprocessor—the 4004 (ref. 1), a modest 4-bit CPU (central processing unit) with 2,300 transistors fabricated using 10 μm process technology in silicon and capable only of simple arithmetic calculations. Since this ground-breaking achievement, there has been continuous technological development with increasing sophistication to the stage where state-of-the-art silicon 64-bit microprocessors now have 30 billion transistors (for example, the AWS Graviton2 (ref. 2) microprocessor, fabricated using 7 nm process technology). The microprocessor is now so embedded within our culture that it has become a meta-invention—that is, it is a tool that allows other inventions to be realized, most recently enabling the big data analysis needed for a COVID-19 vaccine to be developed in record time. Here we report a 32-bit Arm (a reduced instruction set computing (RISC) architecture) microprocessor developed with metal-oxide thin-film transistor technology on a flexible substrate (which we call the PlasticARM). Separate from the mainstream semiconductor industry, flexible electronics operate within a domain that seamlessly integrates with everyday objects through a combination of ultrathin form factor, conformability, extreme low cost and potential for mass-scale production. PlasticARM pioneers the embedding of billions of low-cost, ultrathin microprocessors into everyday objects.

Unlike conventional semiconductor devices, flexible electronic devices are built on substrates such as paper, plastic or metal foil, and use active thin-film semiconductor materials such as organics or metal oxides or amorphous silicon. They offer a number of advantages over crystalline silicon, including thinness, conformability and low manufacturing costs. Thin-film transistors (TFTs) can be fabricated on flexible substrates at a much lower processing cost than metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) fabricated on crystalline silicon wafers. The aim of the TFT technology is not to replace silicon. As both technologies continue to evolve, it is likely that silicon will maintain advantages in terms of performance, density and power efficiency. However, TFTs enable electronic products with novel form factors and at cost points unachievable with silicon, thereby vastly expanding the range of potential applications.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We have reported a natively flexible 32-bit microprocessor, PlasticARM, fabricated with 0.8-μm metal-oxide TFT technology. We have demonstrated the functionality of a SoC that has a 32-bit Arm processor fabricated on a flexible substrate. It can piggyback on existing software/tool support (such as compilers) because of its compatibility with the Arm Cortex-M class processors in the Armv6-M architecture, so there is no need to develop a software toolchain. Finally, to our knowledge, so far it is the most complex flexible integrated circuit built with metal-oxide TFTs, comprising over 18,000 gates, which is at least 12× higher than the best previous integrated circuit.

AWS Graviton2-Powered EC2 Instances Now Available (HPC Wire, 2020); https://www.hpcwire.com/2020/06/12/aws-graviton2-powered-ec2-instances/

Additionally, diamond tools have a closer cut tolerance than carbide does. When used in a cutting capacity, such as a diamond hole saw, diamond tools sand and erode the work material. The smoothing effect of diamond tools allows for high tolerance cuts that are exact. A higher thermal conductivity is another hallmark of the diamond tool. They stay cooler longer and better dissipate the heat created by friction. This means they won’t burn the workpiece and damage it. You can even use diamond tools without coolant and they still won’t overheat. This is valuable in keeping the workshop clean and free of slipping hazards.

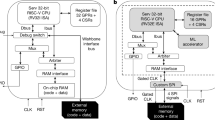

Figure 1b shows the comparison of the Cortex-M used in PlasticARM and the Arm Cortex-M0+. Although the Cortex-M processor in PlasticARM is not a standard product, it implements the Armv6-M architecture supporting the 16-bit Thumb and a subset of the 32-bit Thumb instruction set architectures, and so it is binary compatible with all Cortex-M class processors, including Cortex-M0+, in the same architecture family. The key difference between the Cortex-M in PlasticARM and Cortex-M0+ is that we allocated a specific portion of the RAM in the SoC to the CPU registers (about 64 bytes), and moved them from the CPU to the RAM in Cortex-M in PlasticARM, whereas in Cortex-M0+ the registers remain within its CPU. A large reduction (about 3×) in CPU area is achieved by eliminating the registers from the CPU and using the existing RAM for register space, at the cost of slower register access.

The rest of the SoC consists of memories (ROM/RAM), the AHB-LITE interconnect fabric (a subset of the advanced high-performance bus (AHB) specification) and interface logic to connect the memories to the processor, and finally an external bus interface that is used to control two General-Purpose Input-Output (GPIO) pins to communicate off-chip. The ROM contains 456 bytes of system code and test programs, and has been implemented as combinational logic. The 128 bytes of RAM has been implemented as a latch-based register file and is mainly used as a stack.

a, Layouts of X4 buffers with resistive pull-up (BUF_X4) are shown on the left and layouts of X4 buffers with active transistor pull-up (BUF_X4M) are shown on the right. b, Simulated responses including parasitic capacitance and resistance extracted from the layout. The maximum capacitive load of BUF_X4 is 4.8 pF, based on the data from the liberty file at the typical corner. Buffers with active pull-up can drive much higher loads and consume less static power than their resistive load counterparts at the expense of area increase and reduced output voltage range due to a drop in VDS (the voltage between the drain and source electrodes) across the pull-up transistor. For X4 cells the average static power consumption reduces by 60%, area increases by 43% and the VDS drop is 0.2 V.

a, A simple accumulation program reads values from the ROM and sums them up. If the sum matches the expected value, a confirmation signal is sent to the GPIO output pin that will be read by the tester. The test uses load, add, compare and branch instructions. b, A set of 32-bit integer values are written into the RAM on the fly and reads them back while checking the read values against expected values. If all written values are read correctly, a confirmation signal is sent to the GPIO output pin. The test uses load, store, add, shift, logic, compare and branch instructions. c, A value is read continuously through the GPIO input pin from the tester. The value is masked with a constant value. If the masked result is 1, then a counter is incremented. If it is 0, then the counter is reset. If the counter value is equal to an expected value, then a confirmation signal is sent to the GPIO output pin. The test uses load, store, add, logic, compare and branch instructions. Terms in italics represent variables in the test programs; terms in bold and uppercase are pins and memories.

Understand the difference between diamond core bits and carbide ones. We cover what each bit can do to remove the risk of buying the wrong one.

A few factors will help you determine if you need a diamond or carbide core bit. Not the least of which is what kind of material you want to cut. To cut and grind hardened, super-dense materials, such as granite and concrete, you’ll want to use diamond. Diamond also works best on most non metallic materials such as fiberglass and composites.

Kurokawa, Y. et al. UHF RFCPUs on flexible and glass substrates for secure RFID systems. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 43, 292–299 (2008).

The data that generated the waveforms in the test and validation is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Jang, H.-W., Kim, G.-H. & Yoon, S.-M. Analysis of mechanical and electrical origins of degradations in device durability of flexible InGaZnO thin-film transistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2, 2113–2122 (2020).

Myny, K. et al. 8b thin-film microprocessor using a hybrid oxide-organic complementary technology with inkjet-printed P2ROM memory. In IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC) 486–487 (IEEE, 2014).

We migrated from 1.0-μm design rules to the new FlexIC 0.8-μm design rules to reduce area and, hence, increase yield. As this meant redrawing each cell in the library with smaller transistors, we took the opportunity also to change the standard cell architecture to include MT1 (metal-tracking 1) pins to make it easier for the router to hook up the cells. Improvements to the resistive material (higher sheet resistance, Rs) also enabled a 3× reduction in the size of the resistors.

Myny, K., van Veenendaal, E., Gelinck, G. H., Genoe, J. & Dehaene, W. An 8-bit, 40-instructions-per-second organic microprocessor on plastic foil. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 47, 284–291 (2012).

The Story of the Intel 4004 (Intel, 2021); https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/history/museum-story-of-intel-4004.html

The implementation and measured circuit characteristics of PlasticARM are shown in Table 1, and are compared to the best previous natively flexible integrated circuits built with metal-oxide TFTs7,16,18. PlasticARM has an area of 59.2 mm2 (without pads), and contains 56,340 devices (n-type TFTs plus resistors) or 18,334 NAND2-equivalent gates, which is at least 12 times higher than the best previous integrated circuit (that is, binary neural network (BNN) FlexIC). The microprocessor can be clocked at up to 29 kHz and consumes only 21 mW, which is predominantly (>99%) static power, with the processor accounting for 45%, memories 33% and peripherals 22%. The SoC uses 28 pins, which include clock, reset, GPIO, power and other debug pins. There are no dedicated electrostatic discharge mitigation techniques used in this design. Instead, all inputs contain 140-pF capacitors, whereas all outputs are driven by output drivers with active pull-up transistors.

Karaki, N. et al. A flexible 8b asynchronous microprocessor based on low-temperature poly-silicon TFT technology. In IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC) 272–273 (IEEE, 2005).

a, The SoC architecture, showing the internal structure, the processor and system peripherals. The processor contains a 32-bit Arm Cortex-M CPU and a Nested Vector Interrupt Controller (NVIC), and is connected to its memory through the interconnect fabric (AHB-LITE). Finally, the external bus interface provides a General-Purpose Input-Output (GPIO) interface to communicate off-chip with the test framework. b, Features of the CPU used in PlasticARM compared to those of the Arm Cortex-M0+ CPU. Both CPUs fully support Armv6-M architecture with 32-bit address and data capabilities and a total of 86 instructions from the entire 16-bit Thumb and a subset of 32-bit Thumb instruction set architecture. The CPU microarchitecture has a two-stage pipeline. The registers are in the CPU of the Cortex-M0+, but in the PlasticARM the registers are moved to the latch-based RAM in the SoC to save the CPU area of the Cortex-M. Finally, both CPUs are binary compatible with each other and to other CPUs in the same architecture family. c, The die layout of PlasticARM, denoting the key blocks in white boxes such as the Cortex-M processor, ROM and RAM. d, The die micrograph of PlasticARM, showing the dimensions of the die and core areas.

The first attempt to build a metal-oxide TFT-based processing element is an 8-bit arithmetic logic unit, which is a part of the CPU, coupled with a print-programmable ROM fabricated on polyimide15,16. Very recently, Ozer et al.7,17,18 presented natively flexible dedicated machine learning hardware in metal-oxide TFTs. Although the machine learning hardware18 had the most complex flexible integrated circuit (the FlexIC) built with metal-oxide TFTs at around 1,400 gates, the FlexIC was not a microprocessor. A programmable processor approach is more generic than machine learning hardware, and supports a rich set of instructions that can be used to program a wide variety of applications from control codes to data-intensive applications including machine learning algorithms.

This simple standard cell library was then successfully used as the target technology to implement the PlasticARM SoC using a typical silicon integrated circuit design flow based on industry standard electronic design automation tools. The standard cell library contents and cell usage information are shown in Extended Data Table 1.

Microprocessors are at the heart of every electronic device, including smartphones, tablets, laptops, routers, servers, cars and, more recently, smart objects that make up the Internet of Things. Although conventional silicon technology has embedded at least one microprocessor into every ‘smart’ device on Earth, it faces key challenges to make everyday objects smarter, such as bottles (milk, juice, alcohol or perfume), food packages, garments, wearable patches, bandages, and so on. Cost is the most important factor preventing conventional silicon technology from being viable in these everyday objects. Although economies of scale in silicon fabrication have helped to reduce unit costs dramatically, the unit cost of a microprocessor is still prohibitively high. In addition, silicon chips are not naturally thin, flexible and conformable, all of which are highly desirable characteristics for embedded electronics in these everyday objects.

As we do not yet have a dedicated static random access memory FlexIC, we created a simple register file by carefully placing some modified standard cells in a tiled array that connected by abutment to form a 32 × 32 bit memory (this block can be seen in the chip layout in Fig. 1c).

This processor fully supports the Armv6-M instruction set architecture, which means that the code generated for a Cortex-M0+ processor will also run on the processor derived from it. The processor comprises the CPU and a Nested Vector Interrupt Controller (NVIC) tightly coupled to the CPU, handling interrupts from external devices.

Our approach is to develop the microprocessor natively using flexible electronic fabrication techniques, also termed a natively flexible processing engine7. The flexible electronics technology we used to build the natively flexible microprocessor described here consists of metal-oxide TFTs on polyimide substrates. Metal-oxide TFTs are low cost and can also be scaled down to the smaller geometries required for large-scale integration8.

The RTL simulation is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3. It starts by resetting the PlasticARM to a known state by setting a RESET input to ‘0’. Then, RESET is set to ‘1’, the processor is released from its reset state and starts executing the code from ROM. At first, the GPIO[0] output pin is toggled once before the three tests described in Fig. 2 are executed. In the first test, data are read and added to an accumulator from the ROM, and the sum is compared against an expected value (see Fig. 2a). If values match, a short burst of two pulses is sent to GPIO[0] as shown in Extended Data Fig. 3a. If values are different, the period and duty cycle of pulses on GPIO[0] is increased in Extended Data Fig. 3b. In the second test (Fig. 2b), data are written to RAM, read back and compared. If data has not been corrupted while writing or reading from the RAM, a short burst of three pulses is sent to GPIO[0] as shown in Extended Data Fig. 3a. If data was corrupted, the period and duty cycle of pulses on GPIO[0] is increased as before. In the final test (Fig. 2c), the processor enters an infinite loop and measures the time a ‘1’ is applied on the GPIO[1] input pin. If GPIO[1] is held at ‘1’ without any glitches for long enough, GPIO[0] changes from ‘0’ to ‘1’. PlasticARM was implemented with a clock frequency of 20 kHz. Since it does not use any timers, a value was chosen in software to represent the GPIO[1] signal being held at ‘1’ for approximately 1 s when operating at 20 kHz. In our simulations in Extended Data Fig. 3a, that value corresponds to 20,459 clock cycles, which at 20 kHz yields 1.02295 s.

The FlexLogIC process is an NMOS process and so relies on a resistive load to pull the cell output towards the power supply to drive a logic 1. As a consequence of this, the cell output rise times are much slower than the fall times and this asymmetry can affect performance, especially for heavily loaded nets. To improve the timing on critical nets, such as the clock, we added buffers with an active transistor pull-up. Although these active pull-ups increase the area by a small amount, they do have the added benefit of reducing the static power consumption. Layouts and simulated transfer characteristics of buffers with resistive pull-up and active transistor pull-up are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Wachter, S., Polyushkin, D. K., Bethge, O. & Mueller, T. A microprocessor based on a two-dimensional semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 8, 14948 (2017).

The chip architecture of PlasticARM is shown in Fig. 1a. It is a SoC comprising a 32-bit processor derived from the 32-bit Arm Cortex-M0+ processor product20, memories, system interconnect fabric and interface blocks, and an external bus interface.

18581906093

18581906093